Interview with Gabriella Panuccio, coordinator of the IIT research line “Enhanced Regenerative Medicine”

Name: Gabriella

Surname: Panuccio

Place of birth: Roma, Italia

Position: PI, Enhanced Regenerative Medicine

What does your research team do?

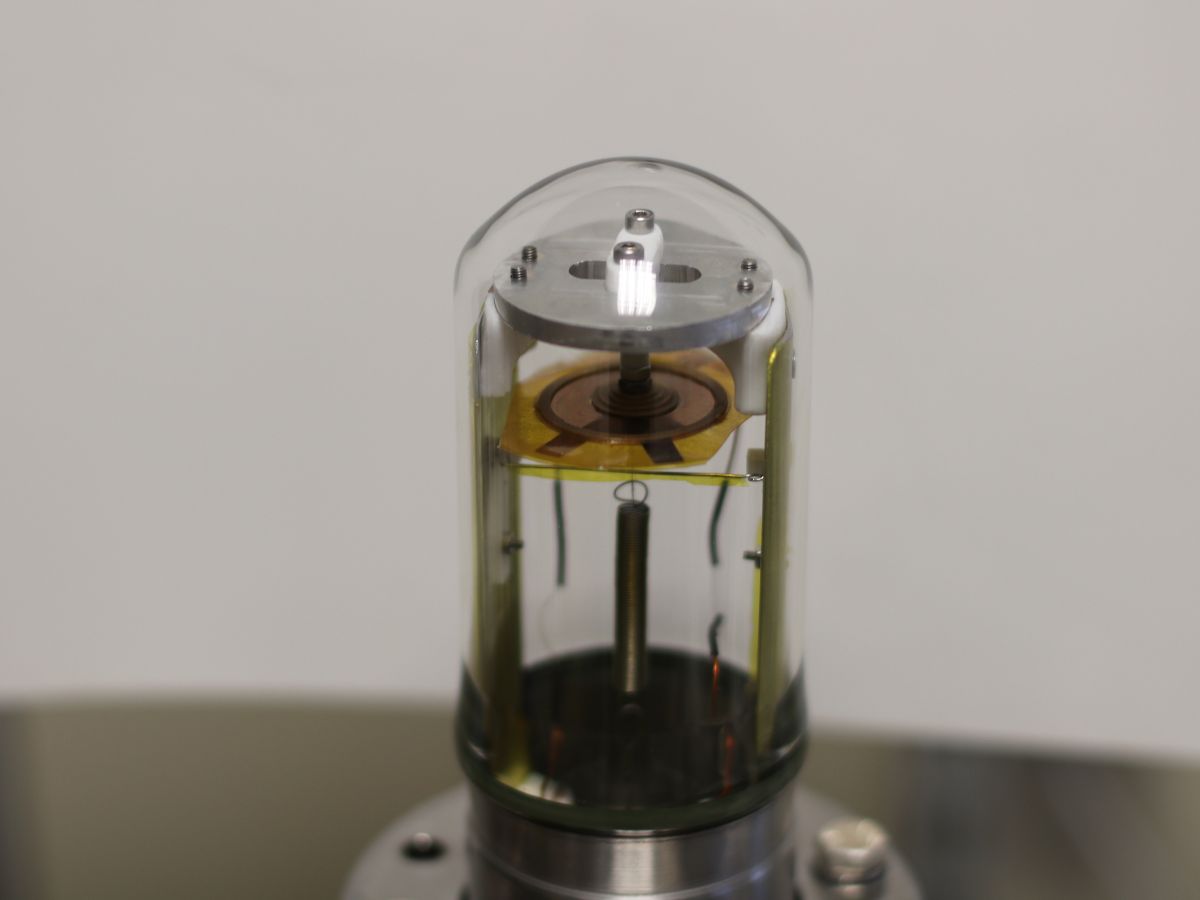

We develop bioartificial systems for brain regeneration. To date, brain damage cannot be fully, effectively and safely healed and the only thing we may do for people affected by brain disorders is help them improve their symptoms with the use of medications, if available, or of electronic devices that stimulate the brain (so-called neuroprostheses), as for Parkinson’s disease. Our mission is to achieve that conceptual leap that will shift the paradigm of medical interventions from treating to healing brain disorders that are to date incurable. Our dream is that we will be able, one day, to heal brain damage by means of tissue transplants, a reality that is only possible to date for other organs of the human body, like the skin. In pursuing our mission, we are part of a large collaborative European project, which merges concepts and methods from regenerative medicine, neuroprosthetics and artificial intelligence.

Regenerative medicine is a branch of health sciences that uses of stem cells or tissues grown in the lab to repair or regenerate organs. Within my team, we investigate how to generate brain tissue replicas, we study their electrical function and their interaction with native brain tissue.

As a purely biological approach, regenerative medicine poses many challenges, because we don’t know yet how to replicate a specific part of the brain, nor can we precisely control how the bioengineered brain tissue will integrate into the patient’s brain. Most importantly, the brain tissue graft needs time to fully integrate itself within the host brain, which remains technically diseased until the integration process is complete. For this reasons, in collaboration with the other project partners, we are developing neuromorphic neuroprostheses, i.e., electronic devices to be implanted in the graft to emulate and integrate brain function (hence, ‘neuro’ -morphic). These devices act as the artificial counterpart and the Guardian Angel of the transplanted brain tissue, guiding its integration within the host brain to be repaired and preventing the brain tissue graft from being entrained by pathological activity that may still be generated by the host brain along the repair process. In addition to this, we are developing artificial intelligence algorithms as a very powerful approach to understanding the dynamics of brain function and dysfunction, with the aim of deploying them within the developed neuroprostheses. This means that the neuroprosthesis may perform well beyond what it would normally do if pre-programmed by the physician, since this is done in a trial-and-error setting, and according to our current knowledge of brain function. Without artificial intelligence, capable of predicting and dealing with the unexpected, it would be hardly possible to adjust the neuroprosthesis behavior in order to handle sudden changes in brain dynamics right on the spot.

These elements altogether yield an enhancement of regenerative medicine for the brain, hence, the name of my research line, Enhanced Regenerative Medicine.

When you were younger, was this the job you had in mind?

I’ve always been very curious, and also fond of science and math. I was among those children always asking “why?” and disassembling toys to understand their mechanism. I didn’t clearly see the word “Scientist” in my mind, but since I was a child, I’ve had in mind this idea of understanding how the brain could control our body and mind as a whole. It was such a mysterious thing for me, and enigmas have always caught my attention. And because, as a child, my father told me that the brain cannot be repaired, as a “why?” child I wanted to understand why and how this could become possible in the future. It was a challenge for me and I was up to it. I was also very curious about electricity and particularly of understanding the electricity of the brain. So, no, I didn’t have in mind “I want to be a Scientist”, that became clear later on when I was at high-school; but I had an innate aptitude for Science. I chose to study Medicine to understand how the brain works and how its function and dysfunction affects the body as a whole, then I got a PhD in Biophysics to study brain bioelectricity, and from there I pursued my roadmap to embrace computer science and neural engineering. Eventually, things unfolded and now here I am, leading a project that puts together all these ingredients.

If this wasn’t your current job, what would you have liked to do?

To be honest this is a very tough question! I honestly can’t see myself doing anything else than this. Being in the lab makes me feel at home. I could as well work as a medical doctor, but then I wouldn’t be researching for new solutions to long-standing problems, whereas I’ve always wanted to be in the frontline facing challenges. My natural aptitude and personal mission is doing something creative, independent and useful to others, something that involves unveiling mysteries, making discovering, and create something new. Science, and particularly the research I conduct now, is the only profession that can give me the perfect balance between creativity and rationality, that is useful to others and allows me to merge all my passions for neuroscience, math, engineering, computer science, and, not least important, medicine.

That time you would have wanted to drop everything and do something else:

Life is made of ups and downs, good times, bad times, and hard times. I actually never considered quitting Science, as I see it as my mission. And during bad or hard times I’ve always said to myself “keep going”. I see challenges as opportunities and I’m known among friends for never dropping the bone. I never did, and it was definitely worth it.

“Publish or perish”. How does the pressure to publish influence your days and your professional choices?

I personally believe that this is not the best and most appropriate way of judging the value of a Scientist. Unfortunately, many funding bodies and hiring institutions look more at the numbers than at the quality and resonance of the published work. So, in a way, this might affect the progress of my research if I don’t keep the pace with publications. But it doesn’t worry me much, nor does it affect my professional choices at all. The most important thing of publishing is sharing research with others, to be useful to the scientific community and, ultimately, to societal progression. In this, inspiration, motivation, and integrity are fundamental, and I consider them a priority over ‘publish or perish’.

When did you realise you were going in the right direction?

After my first post-doc, I decided to shift gears and embark on the field transition I deemed necessary to pursue my scientific vision. Some ingredients were missing, and I felt the need to fill a gap of knowledge and competences in order to have a clearer picture of the necessary ingredients to achieve my vision of healing brain damage. My second post-doc in the Theoretical Neurobiology and Neuroengineering lab lead by Michele Giugliano at University of Antwerp and then my third post-doc as Marie Curie Fellow here at IIT in the Neural Interfaces and Network Electrophysiology lab lead by Michela Chiappalone were both game-changer steps for me, as they gave me a series of invaluable opportunities both in terms of personal and professional growth, and also helped me expand my collaborative network. I knew I was going to step outside of my comfort zone, but that didn’t scare me at all, actually, I was enthusiastic. During these post-docs, I saw things unfold in terms of my growth as a multisciplinary scientist. I started seeing my roadmap more clearly and I realized that I was actually blending together the required ingredients to pursue my scientific vision. This choice indeed triggered a positive chain reaction, thanks to which I am now a PI and I coordinate a multidisciplinary team of European scientists merging all the different expertises I have familiarized with thanks to my field transition. We are all truly committed to what I consider my dream project and I feel very lucky. I’m convinced that I’ve made the right choice in taking that direction.

What is the toughest aspect of your job?

It’s knowing that, while laying the foundation for new therapies of the future that may give new hopes to people, it will take years to reach there. I often get contacted by people asking me if I can do anything to help them, but I know we are just at the very beginning of a very long research journey. It makes me feel sad and frustrated and it gives me that sense of powerlessness because I can’t help those people in this very moment. In research, years-long investigations are the norm, but for people living with an incurable brain disorder even one day could be a nightmare.

Senior researchers necessarily have to deal with many bureaucratic aspects. Apparently, this aspect does not fit well with the research activity. How is that for you?

Terrible. At times I wish I were still a post-doc… It says it all. But it’s still worth it, because now I have my own team, I can pursue my vision and, most importantly, I can pass my experience on to my students.

Who would have to invest more in research compared to what it is done today?

Being in Italy and being Italian in origin, I think that the Italian Ministry of Health as well as the Italian Ministry of Education should invest more, both in terms of funding opportunities and budget. Given what is available now, the idea of pursuing scientific research with low-budget scattered calls is quite unrealistic. In the wider EU context, I think that we are currently heading towards more application-oriented research where the technology readiness level is already very high. I have the feeling that the majority of calls for funding tend to skip on the basic research step, which is an absolute, fundamental pre-requisite for the technological progress of our society. It seems to me that our society in general would rather take the egg today than the chicken tomorrow, and that the long and winding road of basic scientific research towards a new technology is kind of disregarded. But it is fundamental to bear in mind that the technology we have today is here thanks to the pioneering work of scientists pursuing basic scientific research. If Marie Curie hadn’t pursued her work in chemistry and physics, today we wouldn’t have X-rays and all the technology that has derived from her pioneering discoveries.

Do people talk about science outside the labs and the academic world?

Yes, a lot! Typically, when I talk to people who are not scientists and it turns out that I’m a scientist, they become very curious and eventually we talk about science. There is much curiosity about what scientists do, how their everyday life in the lab is, about emerging technologies and new medical therapies. I think people are fascinated by Science and technology and are somewhat mentally projected towards a future of previously unimaginable technologies and hopes to heal incurable diseases.

Who gave you the most important advice during your journey?

I remember four fundamental pieces of advice that helped me become who I am today. The earliest and most influential was my former pediatrician telling me as a teenager “In life, you have to create a goal”. At that age, I had Neuroscience in mind already and he made me realize that I needed to roadmap my baby steps towards becoming a Neuroscientist. That’s when I started my journey with a goal-oriented, structured mindset. I started seeing my future under a different perspective.

Back then, I was at high-school and it was time to decide which direction to take at the University. My best friend was 100% sure that I was made for the Faculty of Medicine and Surgery. Eventually, I took her advice, and now, thanks to her, I have a medical background that I consider an asset for my research.

Equally important was the advice that my mom gave to me after I graduated in Medicine. I wanted to take another degree in Physics/Cybernetics or Electronic/Computer Engineering, but she encouraged me to pursue my roadmap towards the PhD. She knew I wanted to become a scientist and if I had embarked on another university degree I would have been delayed in reaching my goal.

At last was a friend of mine who encouraged me to pursue the PhD in Biophysics, because it was my greatest desire. At that time, I had other opportunities in terms of PhD discipline, but he told me “Follow your dream, regardless of other opportunities arising. It will pay off in the future, as you’ll become what you aspire to be”.

It’s thanks to them that I am here now, carrying my identity as a multidisciplinary PI.

What would you say to the younger you finishing his PhD?

Be inspired and don’t be afraid to make that giant leap to step outside of your comfort zone.

Is working in different countries essential for a researcher?

I can only speak on a personal level. It made a big difference for me, if I compare myself to those who’ve always remained in the same place since the inception of their career. I’ve actually spent more time abroad than in Italy (almost 9 years before coming back as a Marie Curie Fellow). Living and working abroad is a great opportunity to get to know different societal mindsets and organizations, as well as different work management structures. It’s an eye-opener experience that will ultimately help you become more flexible in adapting to different environments. It also helps expand the collaborative network. I would definitely recommend spending a good period abroad, but I don’t judge negatively those who haven’t done so. It’s a matter of personal choice and preference.

You can improve one aspect of research in general. Which one would you choose?

I think that lack of scientific integrity is an important issue, especially nowadays thanks to ‘Publish or Perish’. Predatory journals take advantage of the ‘Publish or Perish’ mindset, making things even worse. Of course I’m not saying that all scientists lack scientific integrity, far from me saying this. But it is a known issue. In this I count in, among others, the long-standing problem of authorship and corresponding author, exploiting a collaborator’s ideas without permission, publishing non-rigorous studies, faking or tweaking scientific results. It seems to me that there is more competition that collaboration, whereas the only race we, as scientists, should run, is that towards scientific and technological progression, together, as a team.