Gaining a detailed understanding of how the brain works means being able to reconstruct, with precision, the circuits that coordinate perception and action. This goal is now within reach thanks to cutting – edge techniques, available in only a few laboratories worldwide, that combine fluorescent proteins capable of labelling neurons with engineered viruses that transport these markers from one cell to the next. Using these tools, Federico Rossi – a neuroscientist and head of the FANCi lab at the Italian Institute of Technology in Rovereto – can record neuronal activity in vivo and in real time, as the brain issues commands and generates responses. This approach is opening the way to a much more precise understanding of the role played by individual neural network

Youthful appearance and unmistakable Tuscan accent, Federico Rossi strikes at first not only for his scientific track record, but because of his friendly demeanour and enthusiasm. I managed to meet him in between the many commitments that fill the schedule of a young researcher who is already firmly established in his field – and, above all, deeply passionate about his work.

After attending the “Francesco Redi” science – focused high school in Arezzo, an experimental track with an enhanced emphasis on scientific subjects, and earning a degree in neurobiology at the Scuola Normale Superiore in Pisa, Rossi embarked on a long international research path. He first moved to Harvard during his master’s degree, then spent almost twelve years at University College London (UCL), one of Europe’s leading centres for neuroscience. There he completed his PhD and several years of postdoctoral research, specialising in circuit and systems neuroscience.

He now leads the Functional Architecture of Neural Circuits lab – known as the FANCi lab, a pun evoking curiosity and imagination – at the Italian Institute of Technology in Rovereto. The lab is funded by IIT, the Armenise Harvard Foundation (which had already supported Rossi’s first stay at Harvard), and Human Technopole, through an Early Career Fellowship awarded in 2022.

At the heart of Rossi’s research lies a simple but far-reaching question: how is the brain organised, and how does this organisation give rise to function? More specifically, what is the relationship between the structure of a neural network and the tasks it performs? To address these questions, his group relies on highly advanced imaging techniques that make it possible to observe the nervous system at work, in real time and with extraordinary resolution, tracing the flow of signals and the connections between individual neurons.

Listening to Rossi describe his work feels like opening a window onto a complex and fascinating world, rich in promise.

«The nervous system may be the most fascinating structure found in nature,” he says. “In humans, it consists of billions of neurons exchanging electrical and chemical signals through thousands of connections. Even at the level of individual cells, neurons are mezmerising, with their branching extensions – they look like trees, with crowns and roots, although they serve a completely different purpose. The real challenge is understanding why they are built this way, which connections shape their activity, and, ultimately, how structure and function are linked».

Is that a bit like figuring out how an electronic device works?

«Exactly. Studying neural circuits is like trying to understand how a radio or a computer works without having its circuit diagram. If you want to understand or repair a radio, you need to know its components, what each part does, and how they are connected into functional modules. Neuroscience is trying to do the same thing for the brain: to reconstruct its functional wiring diagram. The difference is that, in this case, we do not have an instruction manual».

What do we already know, and what remains to be discovered?

«We know that every perception, thought, or movement corresponds to the activation of specific groups of neurons. Different neurons respond, for example, when we see something moving left or right, or when we move in one direction rather than another. What we still lack is a clear understanding of how different cognitive functions depend on the properties of different neuron types and on the architecture of the networks that channel activity through the brain. In other words, we do not yet have the brain’s circuit diagram. Our work focuses in particular on brain regions involved in vision and in the coordination between visual input and movement. The scale alone makes this extremely challenging: a single neuron is about ten microns wide – roughly one tenth of the width of a human hair – and synaptic connections are even smaller».

Your work relies on highly advanced experimental techniques. How do they work?

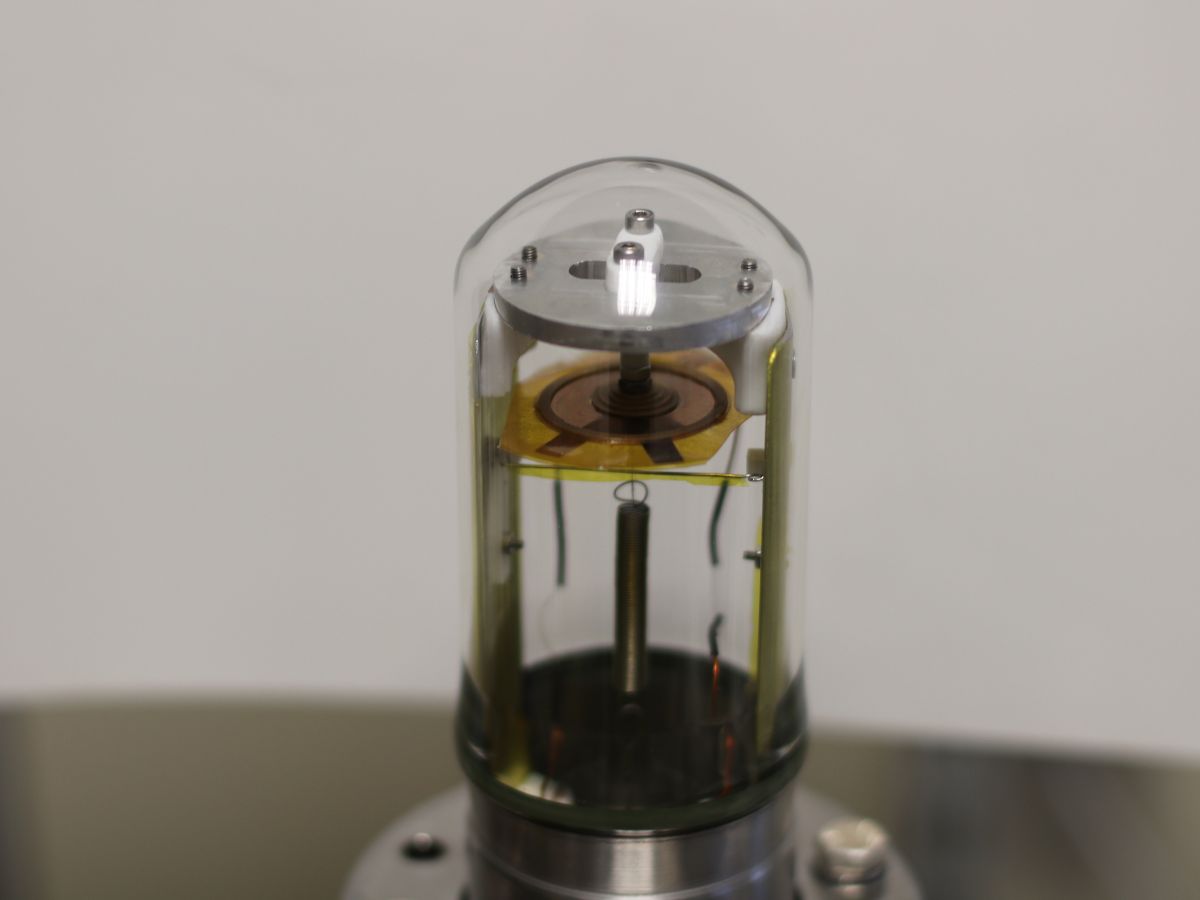

«The core technique in our lab is a fluorescence imaging technique. Using sophisticated microscopes, we can observe neuronal activity in animal model directly while the brain is awake and functioning. Thanks to our experiments we can identify exactly which neurons are active during visual perception and action, producing functional maps with single-cell resolution. This is possible thanks to fluorescent proteins».

So these are proteins with special properties?

«Yes: some make neurons fluorescent, allowing their entire branching structure, dendritic and axonal trees, to be visualised at extremely high resolution; others respond to neuronal activity: as a neuron becomes active and exchanges electrical signals, the protein lights up. The result is a kind of movie in which neurons, with their complex architecture, light up and dim as information is processed – an almost literal visualization of thought in action, reminiscent of a “neural Christmas tree”».

How does this compare with more traditional methods, such as electrode recordings?

«The major advantage is that we can link structure and function directly. We know not only that a neuron is active, but exactly what kind of neuron it is and how it is connected. A distinctive feature of our lab, shared by only a few groups worldwide, is the ability to visualise connections directly. We use engineered viruses, that is, completely non-pathogenic viruses capable of transporting fluorescent proteins, like a kind of biological “postmen” going from door to door: the viruses propagate and, once they have delivered the protein into a neuron, they connect to other neurons along synaptic connections. Starting from a single cell, we can reconstruct the entire network it belongs to. By combining these approaches, we can do something neuroscientists have long dreamed of: record the activity of an interconnected neural network in vivo, while information is actually being exchanged. This makes it possible to isolate specific circuits and ask what they do. One particularly exciting frontier is studying plasticity – how connections change during learning – a defining feature of the brain that sets it apart from artificial computing systems».

What practical implications could this research have?

«A detailed understanding of neural circuits is essential if we want to intervene when things go wrong. Just as you cannot fix a radio without knowing how it is wired, it is difficult to understand brain disorders without a clear picture of how neural networks are organised. Many conditions – such as autism, schizophrenia, or Alzheimer’s disease – are thought to involve disruptions in network connectivity. Another very timely application, especially in vision research, is the development of neuroprosthetic implants designed to restore sight. These technologies require precise knowledge of which neurons to stimulate and where to place electrodes. More broadly, deeper insight into neural circuits is likely to spark new ideas and applications, including ones we cannot yet foresee. Neuroscience has repeatedly shown how fundamental research can have far – reaching consequences. Artificial intelligence is a good example: deep neural networks were originally inspired by the architecture of the visual system, as were their earliest successes in tasks such as image recognition».