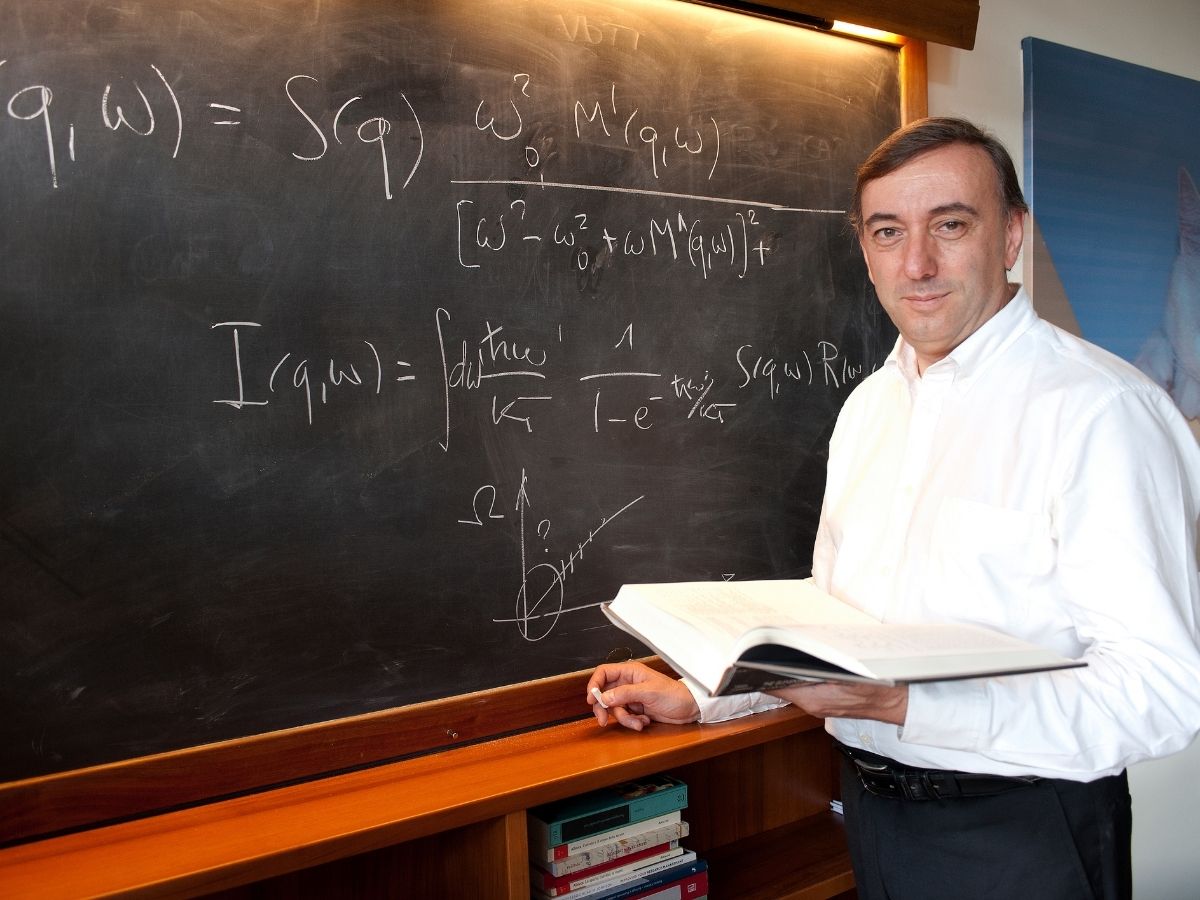

Interview with Giancarlo Ruocco, coordinator of the Center for Life Nano & Neuro Science at IIT in Rome (CLN2S@Sapienza)

How did the story of your laboratory begin?

In 2008, after years during which we hadn’t seen each other, I met Roberto Cingolani. I was the director of the Physics Department at the Sapienza University, and I was soon to become pro-rector for research policy at that university; Roberto was making rapid progress in the organisation of IIT. At that time for the Foundation, the Scientific Director had to locate forms of collaboration, that comprised relations with the academic world, which did not fully understand the role of this new scientific institution. A discussion with Roberto led to the idea of the academy’s greater involvement by means of ‘Seed’ projects. Unfortunately, that approach did not attain the desired results. From that moment on, relations with Cingolani intensified and, following a proposal by the Sapienza University, IIT decided to open a research centre in Rome. This met with a positive response, and we also identified the subject area: medical technology. With the help of several colleagues, I compiled a scientific plan that comprised the concept of work on five specific topics. After consulting IIT’s various scientific and management departments, two of these proposals were chosen: brain tumours in infants, and neurodegenerative diseases. Favourable circumstances enabled us to quickly find the premises, 1,500 square meters, where we are currently working, of state property making up part of the Sapienza building complex. Our research activities began in 2013. Assessments by the authorities responsible for reviewing our work were very favourable right from the start, with just one observation: it was felt advantageous to give IIT a higher degree of cultural independence from the University. This separation, smoothly implemented in close coordination between the parties, led to my request, in 2016, for a sabbatical from the Sapienza University in order to work full-time at the IIT laboratory. In the meantime, the research activities have been restructured, in part moving away from the two initial themes, and the whole structure has focused principally on neuroscience technology. Today, CLN2S comprises seven areas of research, all on neuroscience themes, with varying degrees of focus on technology transfer.

What are the directions of your work today?

I should start by explaining that this centre was founded with a multidisciplinary concept for the medical field, and so we have involved physicians, computer scientists, biologists and physicists; therefore my work has principally concerned enabling people from different areas of culture to work together with the aim of finding a common language. An example, which is possibly banal but can illustrate the level of jargon found in different disciplinary fields: for a physicist the term ‘model’ is a conceptual scheme for representing data. For biologists, with whom physicists are in contact, a ‘model’ on the other hand has four legs and a tail, and it is an organism (very often a rat) that has certain genetic characteristics useful for studying biological processes and pathologies. So I worked on the ‘convergence’ between these individuals, and in the first phase of this process we developed some creative solutions enabling them to work together effectively. In the early years, we launched a competition for some of our colleagues with different scientific backgrounds who, drawn by lot, had to publish a paper together within the space of twelve months. Today, working in convergence is one of the characteristics hallmarking our centre, and so I have been able to dedicate my time to other tasks, such as developing technology transfer, which is certainly less complex. During this process, fundamental for our research, we were fortunate enough to meet an enlightened entrepreneur, Vincenzo Ricco, who, with his small high-tech company, CrestOptics, has financed a joint lab with our centre in order to develop new technology, principally in the areas of microscopy and diagnostics. This activity has enabled some studies to be launched on the market; others, which began later, are following the same route.

So technology transfer will be your strategic objective?

Yes, by continuing to work according to our underlying concept, based on attracting people and ideas, whose development can be assured by means of our technological knowledge. I can mention the case of Salvatore Aglioti, now one of the seven PIs at CLN2S, winner of an ERC Advanced Grant for studies in social psychology (something that is very far removed from TT). He, a psychologist, asked us to work together on the development of certain high-tech products that would help him in his studies, and this is actually happening. Therefore the convergence of two different areas of expertise and culture has taken place, and new physical and conceptual tools are being developed.

What would you need to further improve your centre’s work?

It may seem banal, but at present we are being limited by logistical problems; we need more space for our laboratories. We have been forced to reject applications from new colleagues who wanted to work with us, bringing their own resources and expertise to help the centre grow.

I am convinced that the best approach to work for our institute – which has ‘of Technology’ in its name – is to finance ‘curiosity-driven’ research, which could be described as low TRL, but only in the initial phases. Later, as we have already shown on many occasions, suitable research projects have to proceed by locating industrial or financial partners capable of backing the entire development process up to the market threshold. Research that does not have these characteristics, without doubt fundamental for society’s cultural development, should not be performed at the Institute.