A teenage fascination with both robotics and biology led Luca Berdondini to become an engineer deeply in love with neuroscience. From this early convergence emerged his first groundbreaking invention: microelectronic devices based on the active pixel sensors concept, inspired by digital camera technology. These sensors increased by a factor of one thousand the number of points used to detect the bioelectrical activity of neurons. Today, his work continues on neural devices that can collect ever larger volumes of data while becoming progressively smaller, moving towards a project that sounds almost like science fiction: reducing them to “electronic dust”, transforming them into a myriad of injectable, wireless microscopic devices

Intracortical neural devices – electrodes implanted in the brain to record and transmit its bioelectrical activity – have attracted widespread attention following Elon Musk’s entry into the field with Neuralink. They form the basis of so-called brain–computer interfaces (or BCIs), systems capable of monitoring and translating brain signals into commands for external tools, with a wide range of potential clinical applications. Over time, these devices have undergone an extraordinary evolution.

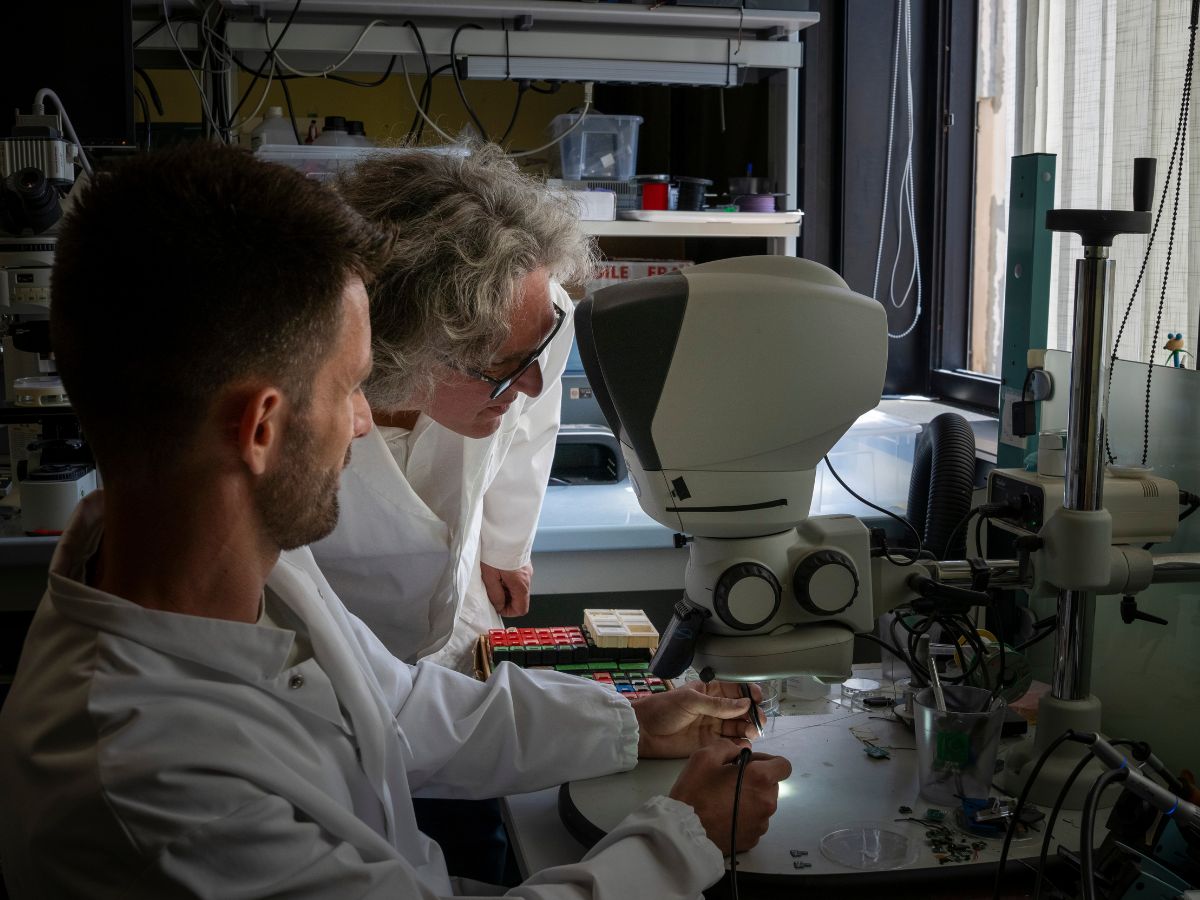

Luca Berdondini, engineer by training and neuroscientist by passion, is Director of IIT-NetS3, the Microtechnology for Neuroelectronics Unit at IIT, where he is now working on next-generation versions of these devices. The field has moved from rudimentary needle-like devices, with only a few electrodes, each connected by a wire to an external instrument, to the exploration of wireless microdevices having the size of dust particles. Berdondini’s work lies at the heart of this shift. We asked him to retrace the path that led to these revolutionary solutions, some of them being used world-wide.

What sparked your interest in neurotechnologies?

«It was driven by passion. As a boy I was fascinated by both robotics and biology. I eventually chose a technological path and studied microtechnology at EPFL in Lausanne. But thanks to a master’s degree at Caltech, working in the lab of a pioneer in microelectrodes, I began studying sensors to measure the bioelectrical activity of neurons straight away. From there, I started developing ideas that were very innovative at the time, and which I later expanded during my PhD at the Institute of Microtechnology at the University of Neuchâtel».

What was the real breakthrough?

«I wanted to create devices capable of integrating a much larger number of electrodes than what was used at that time, so we could monitor the bioelectrical activity of many more neurons and obtain a more precise, detailed view of how they operate in networks and circuits to give rise to the unique capabilities of biological intelligence. I remember presenting my work at conferences and being told by some neuroscientists: ‘Why so many electrodes? A few tens are more than enough.’ But when I was at Caltech, watching cell cultures grow, I kept thinking: ‘There are thousands of cells here, and we are only monitoring a few of them.’ So the real question became: how can I build a device that contains thousands of these electrodes? ».

How did you get there?

«I happened to be in the right place at the right time. In Switzerland, I was surrounded by researchers working on image sensors for digital cameras – like those in our smartphones – which are made of many pixels, each sensitive to light. The idea was to create something similar, but sensitive not to the light, but to the bioelectrical activity of cells. That’s how the first sensors based on the concept of active pixel sensors were developed, with each pixel incorporating a microelectrode and a circuit for signal amplification and conditioning. This led to the first high-resolution planar devices with 4,096 electrodes, which later became the core product of the first startup I co-founded».

And this opened up entirely new research avenues?

«Exactly. These devices can support the growth of cell cultures, or tissues such retinal tissue, as we did in several studies, allowing their functioningto be analysed in extraordinary detail. I have always strongly pursued what we technically call oversampling: collecting more data than strictly necessary, in order to improve signal quality and selectively extract the information of interest. Later, we worked to make these sensors increasingly small and implantable, so that data could be gathered with minimal disturbance to the brain. To give you an idea: Neuralink’s technology requires 64 implants to obtain 1,024 measurement points. We can achieve the same number with a single implant. This result is made possible by microelectronics and micro- and nanofabrication techniques, which allow us to create very small devices with an extremely high density of tiny electrodes».

Do thousands of measurement points really enable a deeper understanding of neural networks and brain circuits?

«Yes, but we are just at the beginning. With a high number of points, it becomes possible to track individual characteristics and their evolution over time: for instance, functional changes in degenerative diseases such as multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s or Alzheimer’s. This lies at the core of my work: a deep interest in understanding how these cellular systems form and organise, the activity they express, how this activity guides their development, how they process information, how they are altered by diseases affecting the nervous system, how we might intervene, and finally how these bioelectrical signals can be used to bridge patients with the artificial world, connecting them to tools that can improve their quality of life».

How is your research evolving today?

«When I joined IIT in 2007, I built my lab by fully embracing the interdisciplinary environment offered by such a large institution. What we are now developing, through both the Crossbrain project funded by the European Innovation Council and the recent Neurobot project funded by ARIA’s Precision Neurotechnologies programme, is the extreme miniaturisation of microdevices. Where these were once planar, they are now integrated as tiny implantable needles, which we are attempting to fragment further to achieve a form of ‘electronic dust’: completely wireless, both in signal transmission and power supply, capable of effectively merging with the tissue itself. These devices will not only detect signals but also actively intervene by delivering precisely targeted stimuli – for example in epilepsy, Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s or brain tumours. These stimuli may be electrical, mechanical or even optical, acting on cellular channels made sensitive to light. Making neurodevices such small is a major scientific and technological challenge. Another application area we have recently started exploring is the peripheral nervous system, to interface signals reaching the periphery – for instance for controlling hand movement. This work is carried out in collaboration with INAIL and with Rehab Technologies, the IIT group specialising in rehabilitation and neuro-robotic prosthetics. Our research is crucial in this domain: robotics can now create machines with multiple degrees of freedom, such as sophisticated artificial hands. The real challenge lies in making their integration as seamless and symbiotic as possible with the natural signals we use to move our own hand – and this is where the interface technology we develop can play her role.»

Have you also commercialised some of these devices?

«Yes. We have created several companies, the most recent being Corticale, to make our implantable SiNAPS technology accessible worldwide. Entrepreneurship is also a way to create job opportunities for the talented young people who work with us, whom we also attract to Italy from abroad and who possess highly specialised skills. It gives them a chance to grow professionally. I still remember what the rector said at EPFL when I graduated: after congratulating us, he added, ‘As engineers, your task is to create jobs.’ That has always stayed with me, and it’s one of the reasons why I have consistently seen a strong bond between research, technology, science and enterprise.»