Interview with Professor Maria Leptin, President of the European Research Council

There were about fifty professionals who had come to Brussels from various European Union countries; amongst the Italians, in addition to myself, there were colleagues from the University of Venice, the Bocconi University, and the Polytechnic University of Turin, all institutes hosting researchers funded by the European Research Council (ERC). The headquarters of the European organisation is located on Place Charles Rogier, not far from Brussels-North railway station. The reason for our meeting was a workshop to discuss the challenges of communicating science, the difficulties encountered in our work and how we can combine forces to raise public awareness of the importance of investment in scientific research. We spent the entire afternoon of 26th April discussing this on the 25th floor of Covent Garden, the glass and steel building looking out over the city rooftops.

Around lunchtime, accompanied by her press advisor, I joined Professor Maria Leptin, President of the ERC from November 2021, in her office one lower down. The office had a large window and a desk covered with documents. Leptin greeted me with a sincere smile and the eyes of someone who had been working hard until a few minutes earlier. In her movements one could sense the energy of a practical person, used to handling interruptions. Later she joined the workshop and the closing toast, exuding friendliness and warmth, never refusing a request for a selfie.

Professor, during a recent event, Wired Health in Milan, Italy, at which you were a guest speaker, you provided an example of the importance of fundamental research, mentioning vaccines for COVID19. In your opinion, what are the ingredients enabling basic research to generate innovation?

First of all, I think it is important to clarify that basic research is not there to develop innovation, basic research is there because the people who do it are curious, they want to find things out. That’s why many people go into basic research. Others work on it because they wish to understand certain facts that are useful for innovation. In general, it is impossible to say where basic research could lead: it is a journey towards the unexpected. To answer the question, I believe that the elements needed for good basic research can be found in the responses provided by the top twenty young researchers selected this year in my own field, the life sciences, who took part in a survey I conducted on the subject. The answers were: funding, independence – complete independence on what is done, when and how; and a good intellectual environment around them.

Could you expand on that?

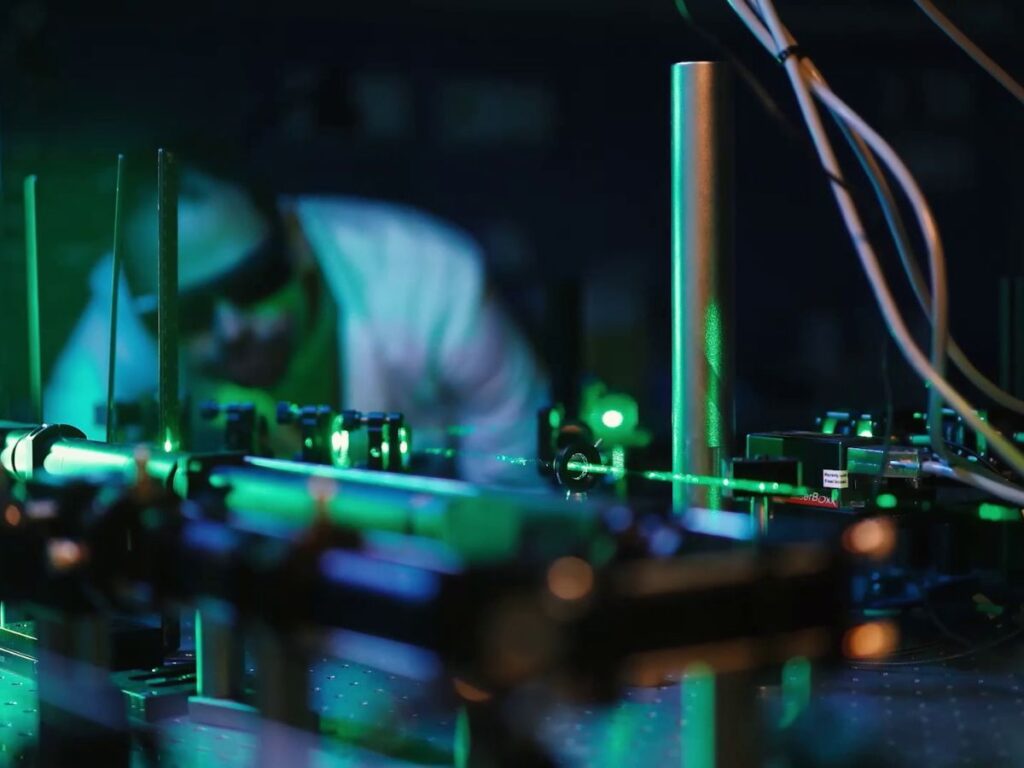

What the young researchers emphasised is that funding should be long-term and not short-term, so that they do not have to spend their time formulating proposals, reviewing them and writing reports, instead of doing research. Funding lasting at least five years, on the other hand, provides a better response to the intellectual efforts of a scientist – writing a proposal and winning a tender competition – who can use the funding independently. And that is precisely what the ERC guarantees. As far as the research environment is concerned, what emerged was the importance of peer assessments, an environment in which colleagues can comment on each other’s work, making suggestions as to what is right or wrong, or the most interesting directions to follow. They want an environment in which they can discuss their research. In addition, support from the infrastructure is important; in other words, they need backing from the institute, they need to know that the laboratory equipment is there – and in the field of life sciences this is obviously very important – and that ancillary staff, such as technicians and administration, are also there to help them.

As you said, the ERC already allows access to this kind of long-term funding, and for younger people there is the Starting Grants scheme. However, these are highly competitive funds and not everyone has access to them. How do you think Europe could support their careers?

Each EU country can play its own small part. There are countries that are funding research better and better and are giving their researchers the same conditions as the ERC. The ERC is not the only organisation providing this kind of funding. But it is also true that if the individual country gives good backing to research, it is far more likely that their researchers will also win ERC funding. It is a positive circle. This is the message that I would like to give to universities, research centres and politicians in Europe: the greater the investment at national level, the greater the likelihood of receiving more ERC grants. However, another significant factor must also be considered, namely good career structuring for young researchers. Repeated three-year contracts, in which you have to report to someone else and the head professor is the “boss” is not a condition that permits young people to grow. This is another point that universities and research institutes should address.

Do you think Europe could do something to encourage such institutions to move in this direction?

I think it is something very local. University careers are defined by each country at a national level. Independent institutes can do something different. But I think Europe could encourage change. For example, the European Commission requires that institutes receiving European funds should have a gender equality plan. But I am not quite sure how much can be done about careers as well.

On the subject of gender equality, I would like to ask you, given your role as a woman in a leadership position, do you have any suggestions for female scientists who are encountering difficulties, or for the younger generation?

I have no specific suggestions, I can only say, do what you like doing, and do it well. It is true that, in 2023, there are still women who do not succeed, but we are also seeing many examples of role models. Recently I met two women in top positions, in Italy your Research Minister, and also the French Minister for Research. The largest international research laboratory, CERN, is led by a woman; the British research funding organisation is run by a woman. Our Commissioner is a woman. All these women I mentioned have children. It is not easy, but it is possible. I think it is now clear that there are no longer any major barriers for women. Everyone can run into problems, even young men. I know many of them who find it difficult to do everything that is required of them. So perhaps we should ask ourselves whether it is not more difficult to embark on a scientific career in general, now that the requests arriving from everyone, from politicians for example, have increased, and bureaucracy has also increased. Scientific careers have become less attractive than a few years ago.

The communication of science is becoming more and more important for the ERC, as demonstrated by the “Public Engagement with Research Award” programme, and the latest “ERC Science Journalism Initiative.” What is the reason for this special attention?

First of all, I wouldn’t say that good communication of science matters to the ERC, good communication of scientific research is important for everybody, for the public, for the whole scientific community, and for politicians. The two ERC initiatives you mentioned are small but important. The first is particularly satisfying because it is inspiring for scientists who want to inform the public about their research; there are many researchers who do this voluntarily and I think it is good to support them, and we are doing so by means of this small prize. We all rely on the public’s understanding of science, so we should continue promoting this kind of activity. But scientists cannot reach all parts of the population, and so by means of the second operation, we are targeting journalists, who have the tools to reach a wider public. Our programme is a way of helping journalists to understand how our world works.

What’s next for the European Research Council?

We have already announced that the ERC is modifying the way it assesses researchers, and this is connected to the support we want to give to the world of research. We have listened to the researchers’ requests. I hope that younger people will see it as a positive thing that the very specific and narrow criteria that have been used up until now to evaluate their work will no longer apply. We will change the information that will be required to submit a project for funding. And this will help the younger researchers – who are in fact the next generation of scientists – but also the more senior researchers. It is important that support for research takes place throughout their whole career. Lastly, what we will have to work on is the next EU framework programme for R&I. I think Europe will have to recognise that more money must be spent on research – doubling the overall budget – in order to be internationally competitive.